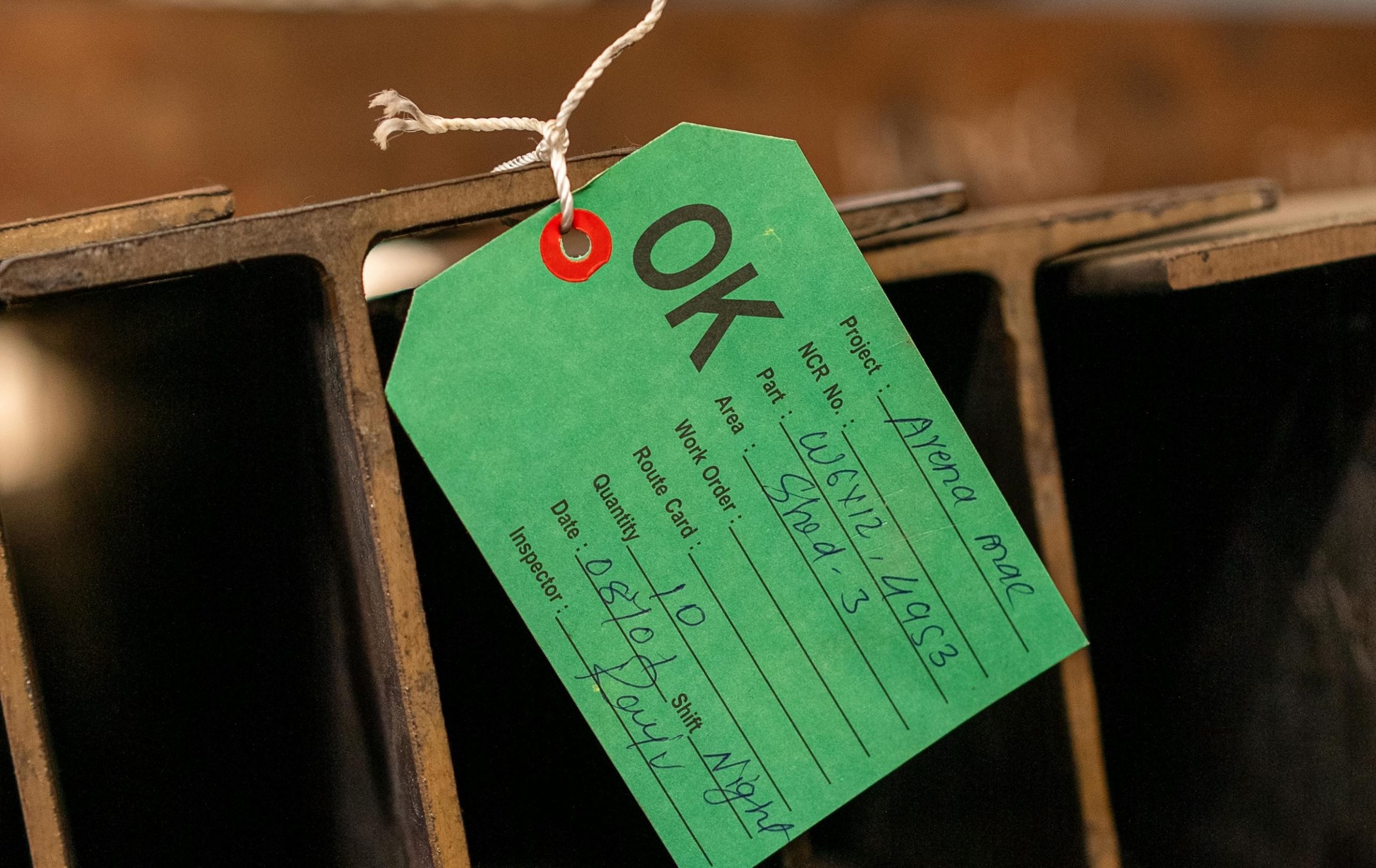

Excessive quality is “muda” – waste. If you’ve been exposed to Lean, you know the seven types of waste. One of the common ones in IT is overprocessing. Building high-quality software for a temporary need is overprocessing.

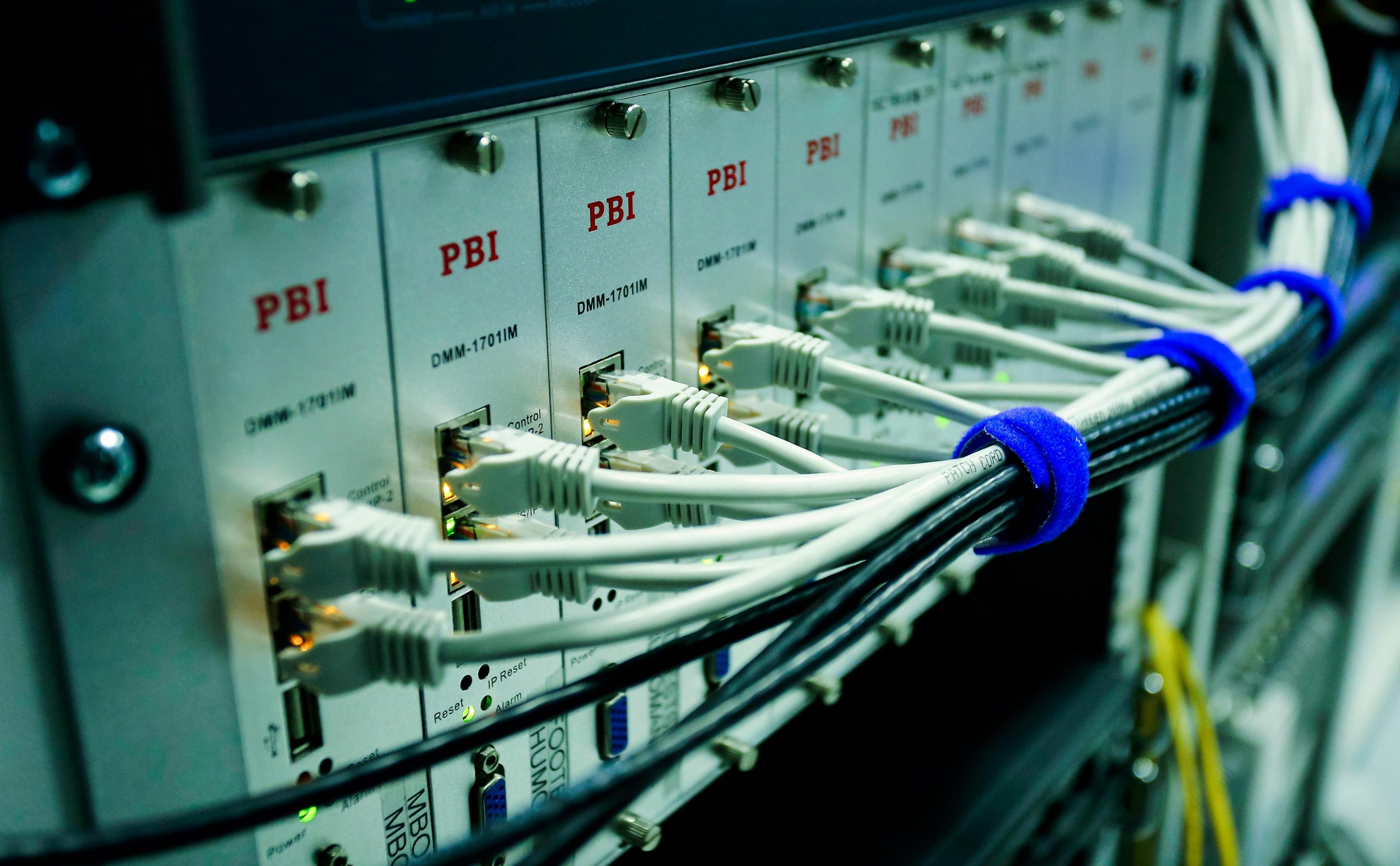

Much of the discussion about crappy AI-generated code fails to make the distinction between critical systems that lives depend upon and which will be maintained for decades, and one-off temporary solutions.

Spending scarce human programmer resources on building tactical, short-lived systems is overprocessing. Let the AI build it.